Steno bredanensis were the strangest and most lovable dolphins that I ever got to know.

My husband, Tap Pryor, founded an oceanarium, Sea Life Park, in Hawaii. It was the early 1960s. The various buildings, tanks, and pools, were built on the sloping base of a cliff, and all faced the sea. Tap hired an expert Hawaiian fisherman, Georges Gilbert, and his assistant, Leo. When the undersea display building was completed, Georges and Leo collected a wonderful variety of coral reef fishes. Then, when the training pools across from the park itself were completed, they went out in their fishing boat to collect dolphins. In next to no time five little spinner dolphins and a couple of big bottlenose dolphins were brought into the training pools for future use in shows for the public. Here the dolphins were taken care of and trained until they were ready to be moved into the show pools and tanks. I was to be the dolphin trainer. I had no experience with marine mammals, but when the people they’d hired to do the work weren’t successful, I was asked to do it. I’d trained other animals, such as dogs and horses, for my own use, and agreed to work with the dolphins.

The oceanarium included a pier, extending out into the water across the highway from the park. Thus the collecting boat and other related vessels could be safely accessible. Meanwhile someone on the park staff painted a life-sized dolphin on the side of the collecting boat.

Tap told me to come take a look.

“That is the ugliest dolphin I have ever seen,” he grumped.

Well, it wasn’t exactly a work of art. The dolphin painted on the side of the boat had a misshapen bulgy head, a long ugly snout, a fat belly, HUGE big flippers and a much-too-big tail. Furthermore, it was painted blotchy brown all over: the real dolphins in our training tanks were all mostly gray.

And then Georges and Leo collected a new kind of dolphin, one that had never before been kept in captivity. As with the other dolphins, this one was caught within a netted loop of rope, lifted on board, put on a stretcher, and kept cool with buckets of salt water. On the way back, Leo played his ukulele to calm the animal.

I happened to be in the training department when it came in. Guess what. This dolphin was blotchy brown and scarred, too, all over. It had a bulgy head, a long ugly snout, a fat belly, HUGE big flippers, and a much-too-big tail. A reporter friend later commented, “Looks as if it spends its finest hours fighting with a switch blade.”

It’s customary to introduce a new dolphin into one of the training tanks with just one other dolphin in there already, to keep the newcomer company. Maybe it won’t be the same species, but at least it will be somebody. A young bottlenose was already in the tank. It was being trained to ring a big bell by bumping it with its rostrum. Bang. Bing! You get a fish. The brown blotchy dolphin was lowered carefully into the tank. It ignored the bottlenose. If hovered across the tank and watched the action. Hmmm. That dolphin is ringing a bell. That dolphin got a fish to eat. The new brown visitor zoomed briskly across the tank, shoved the bottlenose away from the bell, and slammed the bell with its rostrum. And then waited. OF COURSE I fed it a fish right away. And any more that it cared to consume.

We were all a little stunned. It may not be beautiful, but it was damn sharp. This was my introduction to a species that was new to me (and many others in the oceanarium world). I loved it from the start.

We located the Latin name for these animals: Steno bredanensis, the rough-toothed dolphin. Georges and Leo brought in another Steno. The two of them were perfectly comfortable together. We named them Malia and Hou. We began teaching them a few things. They began teaching us a few things.

How about this one:

The tank needed cleaning. An adjoining tank was full of salt water but empty of animals at the moment. The staff decided that the easiest thing to do would be to move the Stenos into the smaller tank by waving fish at them. Well, they wouldn’t go in. So, a couple of staff members got their big net, enough to cross the whole tank. Now the tank was divided in half by the vertical net. The two Stenos were now confined to the right-hand half of the tank, facing the open gate into the tank next door. The staff’s plan was to drag the net across the second half of the tank and force the two animals through that gate into the next tank.

The water is crystal clear in Hawaii, and turns over every hour, so it’s crystal clear in the tank. We watched as one of the Stenos went down to the bottom and lifted the weighted edge of the net. Whoopee, the other Steno swam under the net to the back side. Then the other Steno lifted it and the first one went under. Back and forth, left and right, swimming under the net, they were enjoying their new game.

We were stumped. And then… just when the guys were ready to give up and take the net out of the water, the Stenos both went under the net and swam calmly into the adjoining tank. These animals were telling me what they knew and what they could do. They didn’t even ask for a fish when they put themselves into the smaller tank, but they got some.

From then on we had Stenos in the shows. We moved Malia and Hou to the Ocean Science Theater, a beautiful glass enclosure with a sheltering roof with a hole in the center for a glimpse of the sky. The back wall closed off the trainer’s dressing room and the back of the tank. But the glass wall around the two thirds of the rest of the tank gave the audience, seated in raised rows, a complete view of the animals under water and above water.

One year during December we weighted a Christmas tree and sank it to the bottom of the tank. Then we trained two Stenos to fetch long bright wide ribbons and wind them around the Christmas tree, one winding the ribbons left to right and top to bottom, the other one crossing her ribbon right to left and bottom to top. It made the tree look great and the audience loved it.

Both Malia and Hou were females. The younger one, Hou was timid, and learned new skills slowly. The adult, Malia, was full of ideas of her own. One day she swam up to the side of the tank, looked at the trainer on the platform at the back of the tank, and calmly launched herself out onto the deck. “If the people are having fun out of the water, why shouldn’t I?” It was not a good idea, especially if she decided to do it when nobody was around. Once she had decked herself, she would not be able to back up nor turn around. She would dry off and overheat, which could be fatal.

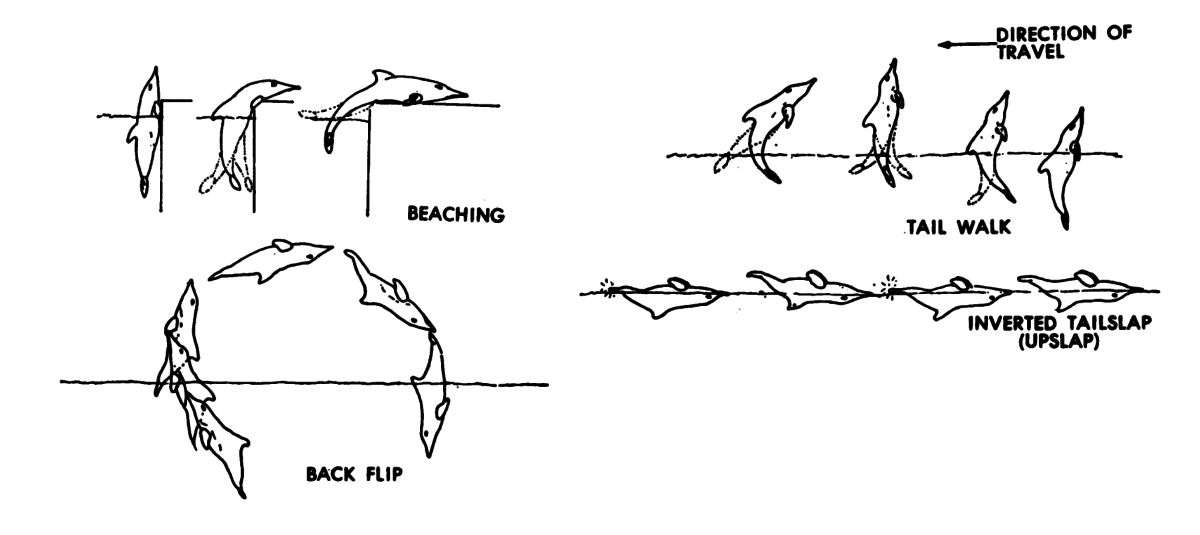

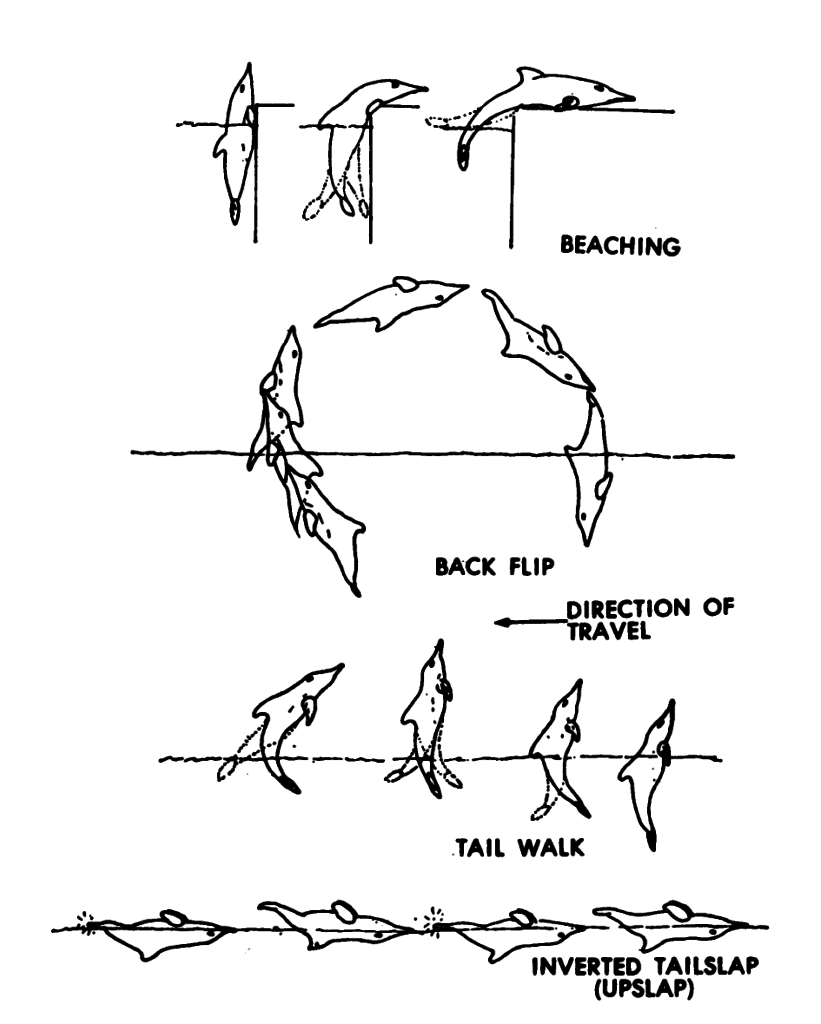

Ingrid Kang Shallenberger, a trainer at Sea Life Park, using a whistle, hand signals, and fish, succeeded in teaching Malia a hand signal for beaching herself on cement, and then, with some manual help from an assistant to return herself to the water. Of course, once that became a trained behavior it was just a job, not the Steno’s idea of a joke, so the dolphin never did it spontaneously again.

There were enough of these sort of interactions, that I had to be this flexible all of the time. I had no assumptions about what the Stenos could do. They showed me. Oh, they were fun! Creativity and thinking is part of who a Steno is. I observed these animals make leaps of thinking. The training sessions were continual conversations with the dolphins. I realized that I could ask the Stenos to show me what they could do. I trained the Stenos, on cue to show me something new.

We decided to show an audience how we ask the animal to think up a new behavior. We turned Malia loose in the big glass Science Theater. She circled around, waiting for a cue. Ingrid stood on the bridge and did nothing. Annoyed, the Steno slapped her tail, Ingrid blew the whistle and tossed a fish. Aha!, that must be what was wanted. Malia slapped her tail again. This time, no whistle and no fish. Nothing else happened for the next minute. And then suddenly the Steno circled fast, turned upside down, and glided in a circle with her big wide tail in the air. It made the audience roar with laughter. For this, the Malia got a whistle and a fish. She had thought it up herself.

This creativity became a regular event. Sometimes when we got to the theater in the morning Malia was wildly excited, splashing and flapping around in her holding tank, dying to show us what she’d cooked up this time. One of us opened the gate. Out she went into the big tank. Now she was jumping in an arc in the air — but upside down! Next day — rotating like a corkscrew through the water. Or boldly flipping head over tail in the air. Here’s a specifically good one: she dived to the bottom of the tank, turned upside down, and used the tip of her dorsal fin to draw lines, in big loops, in the silt on the bottom of the tank.

This is an animal. Just an animal. Scientists did not approve of animals inventing things just to amuse themselves. Well, too bad. She certainly amused us! But, it wasn’t only about fun tricks. No one before had been able to ask an animal to show them creativity. What we did led to ground-breaking work, and eventually to a paper that has become a foundation of creativity research for others. It wouldn’t have been possible without the Stenos.

I left Hawaii in 1976, moved to New York City, and assumed that I’d be out of the dolphin business for good. Not so. In the 1980s I did research to help make the tuna industry safer for dolphins. On various sea voyages during my scientific years I saw a huge variety of marine life, from red swimming octopi to giant blue marlins and toothy killer whales. But the memory of Stenos surfaces most often. I knew and trained Stenos in captivity where I learned about their creativity and intelligence. But seeing them in the wild showed me their full personalities. My favorite memory is this:

Ingrid and I were research scientists on board the fishing vessel Queen Mary, from which we dived in the tuna nets over and over. (We never saw Stenos in our nets, they’re much too sensible for that.) One day the sea was very rough, too rough to set the nets. The skipper told us to relax, the boat would just be idle today.

Nobody was upstairs in the pilot house. Ingrid and I went up there to look at the high waves rolling past us. Well, well, well! There were seven or eight Stenos body-surfing in the big waves in front of our ship. When the wave collapsed those Stenos turned, swam completely around the Queen Mary, got out in front of the ship, and caught the next big wave. They make another 360 around the ship. They catch another big wave and balance themselves half way out of the face of the water. The wave passes. Swim around the ship, catch another wave. We watch them for an hour? A day? A lifetime? And then suddenly they quit, sink under water and depart. Wise animals, full of joy.

References

Pryor, K. W., Haag, R., & O’Reilly, J. (1969). The creative porpoise: Training for novel behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of behavior, 12(4), 653–661.

Pryor, K. W., & Chase, S. (2014). Training for variability and innovative behavior. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 27(2).